Bird Songs Are Not What You Think

The Listers Movie and Bird Time

I recently watched “The Listers” (free on YouTube), an extreme bird-watching documentary, which was both hilarious and eye-opening. The main character has a revelation while he is high on weed to begin bird-watching, and joins the Big Year: an annual bird-watching competition in the United States. We watch him and his friend as they go on a #vanLife adventure, learning how to observe birds, photograph them, record their calls, and document their findings.

The viewers get a glimpse into this world of odd, obsessive characters. I’d highly recommend it.

The Big Year is a numbers game. During the calendar year, you try to find as many birds as possible in the continental U.S. The winner gets the most valuable prize ever: reputation.

Participants use technology, uploading their GPS findings to eBird, where other community members verify that, indeed, you found the bird you said you did.

But What About The Birds?

As fascinating as all that was, what struck me was how little these birders actually seemed to care about the biology of the birds themselves. Beyond whether the bird is shy or not, they didn’t seem to care about the amazing science: that many birds see in ultraviolet, the specific characteristics of each bird, or that, most amazingly, what we hear as bird songs is not at all what the birds actually hear.

The Hidden Timing of Bird Songs

Bird songs may sound like simple melodies to humans, but birds perceive these sounds in a completely different way. They can hear timing — subtle temporal shifts — in ways we cannot. Their brains process the signals more rapidly than we do, so that the beautiful bird songs we hear are only some of the encoded information.

Our brains blur sounds that happen too quickly, such as notes spaced closer than about 25 milliseconds. Birds, on the other hand, process sound at a much higher temporal resolution, about 2 ms, which is around 10 times faster than humans. It’s as if we are hearing in slow motion, compared to them.

The interpretation of bird songs also includes information on different timescales, one around 10–30 ms and another in the 500–700 ms range. This requires auditory processing to be integrated temporally at different scales so the birds can extract critical information about what the bird songs are actually saying.

The encoded information, of course, remains completely unnoticed by us, who only hear a simple melody. However, the information can include many things, such as alarm calls that convey very specific details about predators. For example, chickadees will add up to 23 more “dee” notes to warn of a smaller, more agile hawk or pygmy owl that they see as more dangerous to them based on body size and agility, compared to a slower, larger predator like that of a great horned owl that is less maneuverable in flight and less of a threat to the little chickadees. To us, it all just sounds like a generic “alarm”, but to them, they hear valuable information that allows them to react, adapt, and survive.

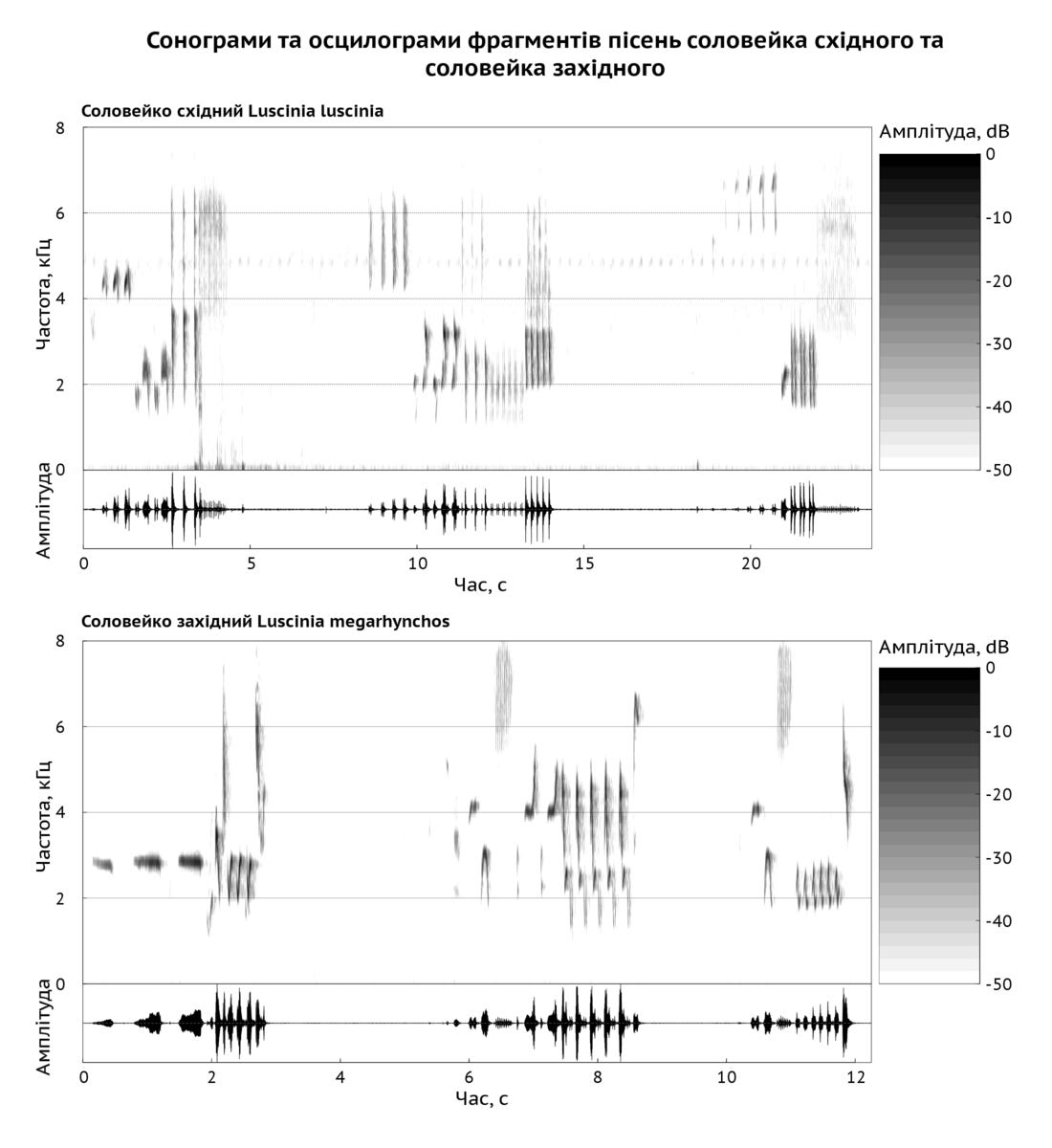

“Sonogram of Luscinia luscinia vs Luscinia megarhynchos, by Yu Moskalenko, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0”

Songs That Speak of Self

Many bird species use songs much like we use our own voices for recognition, distinguishing neighbors from intruders by subtle differences in pitch contour and rhythm that sound identical to human ears.

Within a population of birds, individuals learn from each other and share vocalizations to sing a common dialect within that population. This is not so different from how people in one town might develop their own phrases and dialects that other people in other towns might find different or quirky.

But just as some of us bend the rules of speech to stand out as individuals, bird researchers also found copying errors, perhaps intentional anti-conformity ones that lead to the production of novel bird song features that provide cues to the individual bird’s identity. Some of those new features may become unique signatures of that individual and may even become more culturally and reproductively ‘successful’ than others, and may increase in that local population.

Song performance itself also encodes the quality of an individual: a male that can sustain rapid, precise trills without faltering demonstrates great health and stamina, signaling his fitness to both potential mates and rivals.

Finally, the meaning birds attach to songs is practical and precise. A song is not just a song. Instead, it can mark territory, advertise health and vigor, attract a mate, or convey identity, down to whether the singer is a familiar neighbor or an intruder.

More Than Music

For us, birdsong often exists as background music to a morning walk. It’s pleasant, relaxing, and melodic. But for the birds, it’s a rich, coded, complex language with subtle cues and temporal variations that are essential to their survival and reproduction. What we call music, they experience as communication at its most urgent.

I find this stuff fascinating. Once you start noticing how layered and intricate these songs are, it’s hard not to want to dig deeper into how they work. If you want to learn more, check out Benn Jordan’s YouTube channel, which covers the specific aspect of bird calls and their perception.

I don’t know much about the general birding community, so I’m not too qualified to comment on how the regular birder engages with biology. However, what struck me in Listers was how separate the birders were from the birds, nature, and the birdsongs in so many ways. Like what humans often do, they turn it into a competition, which is fine; it can still be a source of education and entertainment. However, in doing so, they missed out on some amazing biology in their quest to upload images to the app for verification.

This is a really cool explanation and deepens my appreciation for bird song. I spent quite a lot of time the last couple years recording them in the mountains. Love seeing a Benn Jordan reference too. Love that youtube channel, and haven't yet watched the video you linked.