We don’t think about the vibrations of seaweed, or a fern, or mycelium. But we should. Every organism, no matter how still or silent it may appear, emits an electrical field, ever so subtle. These signals might be nuanced, but they tell a fascinating story of energy, growth, and environmental interaction. By capturing these faint patterns as sound, we can hear the “voices” of these unheard organisms, giving us a new way to connect with the living world around us.

Capturing The Sound of Seaweed

I recently captured data from several otherwise unheard creatures using custom sensors that I made.

Sensors on seaweed

My high-quality electrical sensors capture electrical data from seaweed, mycelium, and a fern, and I translate these recordings into ambient soundscapes to reveal the hidden vibrations of these organisms.

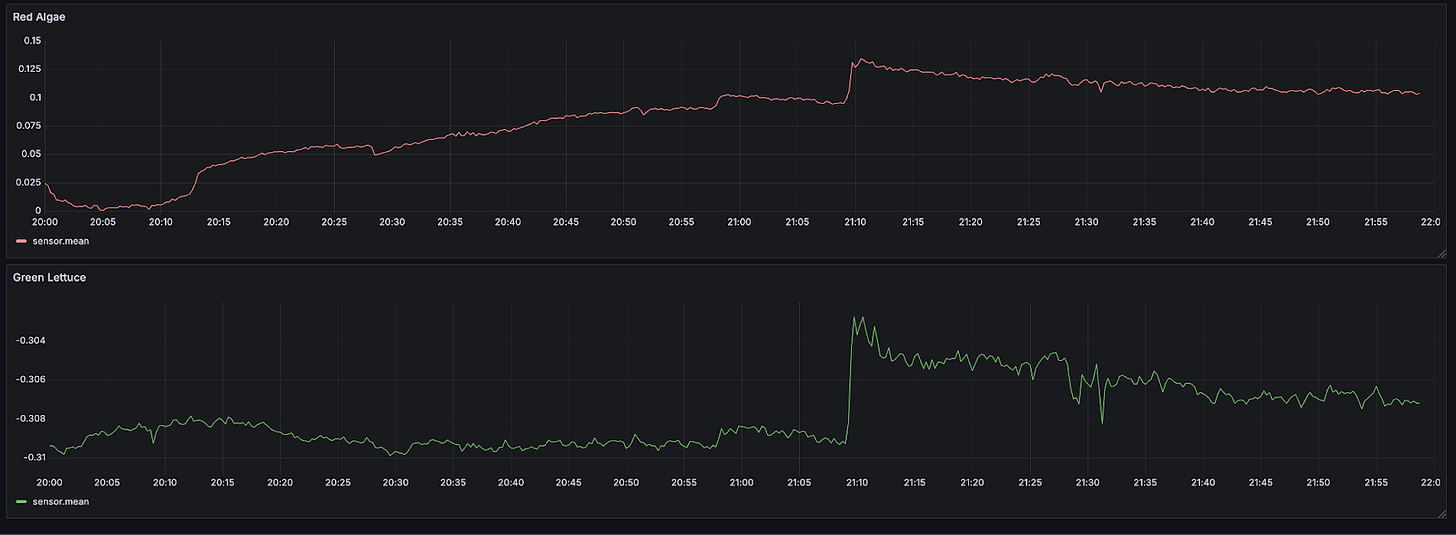

What does the data look like? Something like this, with a pronounced spike at sunset. I don’t even know what’s going on with these sea creatures.

Plot of two different seaweed samples

What Makes The Actual Sounds of Seaweed?

Curious as I am, I did some digging and found scientific studies that may shed light on what’s happening with these seaweeds. While I am translating data from the seaweed into sound, it turns out that seaweeds produce audible sounds as well.

Seaweeds, just like land plants, create energy from the sunlight via photosynthesis. They absorb carbon dioxide and water during the day, using it to produce sugar, which they utilize for energy and growth. Just like animals, their metabolism produces waste. All plants release pure oxygen as a waste product of photosynthesis, the very molecule we need to survive. Oxygen is released dissolved in water or as bubbles of oxygen gas.

During the day, the rate of oxygen production via photosynthesis typically exceeds the rate of oxygen consumption by marine organisms. As a result, in water as in air, as the day goes on, the area around the seaweeds becomes supersaturated with oxygen, and bubbles of oxygen gas form. Studies have found that it’s the formation of these bubbles of oxygen that is the major contributor to the sound that seaweed makes. As bubbles form and reach a large enough size to detach from the seaweed, they create a short ‘ping’ sound that rapidly decays. The continual release of oxygen from countless surface pores on the seaweed creates a sound that you can measure.

Interesting, but what’s going on at sunset?

One might logically assume that as sunset approaches, the rate of bubble formation might slow down as available sunlight decreases.

However, I suspect a couple of things are going on here. One is time. It takes time for those bubbles to reach a certain size to escape the surface tension of the seaweed. Seaweeds have surface features that allow them to hang on to oxygen bubbles throughout the day, which, in water, causes their leaves to float. Different species have distinct surface features, which influence their ability to retain oxygen. This could explain why the green algae produced a stronger peak at sunset than the red, simply because the red is better at holding onto bubbles of oxygen.

Another factor is supersaturation. The area immediately above the surface of the seaweed becomes supersaturated with oxygen after photosynthesizing all day long. At sunset, photosynthesis ceases. That means that the air immediately above the surface is no longer supersaturated, resulting in a significant increase in bubbles being released, and therefore ‘pings’ of sound. The sound gradually declines to a low level overnight as oxygen bubbles continue slowly escaping from the seaweed’s surface.

So, these sounds, or the energetic processes related to photosynthesis, are very likely creating or contributing to the electrical signals that I am recording.

Here’s another interesting little tidbit. Other studies have shown that not only do seaweeds produce sound, but they also respond to that sound with an increased growth rate. This means that when a seaweed is actively photosynthesizing and producing sound, the sound it generates stimulates the other seaweeds around it to grow. Therefore, they also photosynthesize and produce more sounds in a fascinating positive feedback loop of life, sound, and growth.

Sensor-Based Soundscapes Event

I presented my sensor-based soundscapes for the event:

“The Psychedelic Snail, and Other Pollinators You Didn't Know You Needed: A Night of Culinary & Artistic Adventure” at Heron Arts in San Francisco, along with Home Grown, an architectural artwork by Raylene Gorum, and a Sonic Grazing Table by Maria Finn.

We played my soundscapes on silent disco headsets, while the guests ate the very food that they were listening to: ferns, seaweed, and mushrooms.

This was perhaps weird enough for me to reconsider the aliveness of everything, even the plants, which most of us hardly think about. It felt like a merging of science and art. By translating electrical signals into sounds of life and consuming the organisms that produce those sounds, I was inviting people to hear and taste the pulse of life itself, blurring the boundary between them and us and reminding us that everything is alive.

Listen to the Sounds of Seaweed, Ferns, and Mycelium

I also just uploaded the soundscapes to SoundCloud. You can listen to them yourself here:

The Quiet Voices of the Living World

Listening to the fascinating sounds of seaweeds, ferns, and mycelium reminds us that life is constantly communicating, whether we hear it or not. Every single vibration, every little pulse, is proof of its aliveness. These recordings should never be viewed as just ‘background noise.” They bridge the gap between us and the quiet voices of the living world that we so often overlook. Perhaps, if we listen closely, we might find ourselves more deeply connected to the living world and all its wonders.