The First Breathers

Rise of the Cyanobacteria

Imagine an Earth that was dark, hot, and devoid of oxygen, thick with volcanic gases: mainly methane (CH₄), carbon dioxide (CO₂), nitrogen (N₂), and hydrogen sulfide (H₂S). There was no ozone layer (O₃) to block ultraviolet radiation. These compounds scattered and absorbed sunlight, especially in the visible range. The planet’s surface received a dim, reddish light, like a planet orbiting a red dwarf star.

Oceans were filled with dissolved iron, the seas probably looked metallic-green, and the planet glowed a purple hue instead of our familiar greens and blues. Microbial life, like the Purple Bacteria I wrote about last week, appeared mostly as thin films on rocks and sediments. They lived by tapping the chemical energy in sulfur, hydrogen, and other reduced compounds from the thick, dark atmosphere.

The Age of the Cyanos

So what changed the course of life on our planet? We can thank an unexpected microbial evolution for lending us this verdant planet we have today.

The Origin of Oxygenic Photosynthesis

Virtually all modern cyanobacteria, algae, and plants use a dual-photosystem architecture —Photosystem I (PSI) and Photosystem II (PSII) —that defines oxygenic photosynthesis today. This allows plants, algae, and cyanobacteria to capture short-wavelength light in PSII, splitting water molecules into electrons, protons, and oxygen. Then, this dual-photosystem uses PSI to boost the electrons released by PSII, which absorbs a second, longer wavelength of light, reenergizing them to generate the reducing power used to convert carbon dioxide from the air into glucose that the cyanos, plants, and algae use to grow and reproduce.

So how did we get these 2 different photosystems that forever changed the course of life on Earth? Each light-harvesting system came from different prokaryotes.

PSI and Green Sulfur Bacteria

PSI appears to have originated from Chlorobium limicola, a green sulfur bacterium, that has a PSI-like reaction center for its anoxygenic photosynthesis that uses ferrous sulfide (FeS) as the electron donor instead of water. The green sulfur bacteria live deep in the microbial mats, absorbing the longer wavelengths of light that the purple bacteria above do not use.

PSII and Purple Sulfur Bacteria

PSII is believed to have evolved from purple sulfur bacteria, possibly from Proteobacteria and Chloroflexi, that utilize hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) for anoxygenic photosynthesis. These live higher in the microbial mats, absorbing shorter wavelengths of light than PSI.

It’s believed that gene duplication events gave rise to the new proteins that replaced those of the PSI and PSII-like reaction centers for anoxygenic photosynthesis of the ancestral purple and green bacteria, leading to the evolution of PSII, whose unique innovation was to extract electrons not from hydrogen sulfide or ferrous iron, but from water itself. The by-product of this reaction produced oxygen, which, at the time, was toxic to almost everything alive.

“Photo by Willem van Aken / CSIRO Land & Water, under CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)”

The Great Oxidation Event

Originally, these early microbes, cyanobacteria or their ancient ancestors, started producing oxygen in small amounts (< 0.001%) as far back as the Archean eon (4–2.5 billion years ago), predating the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) by about 1 billion years, likely before they acquired both photosystems.

Then, at some as yet unknown point in time, an ancient lineage leading to the age of the cyanobacteria acquired the genes for both PSI and PSII in a single ancestral cyanobacterium. This likely occurred via horizontal gene transfer, a relatively common process in which prokaryotes take up naked DNA, not via the usual routes of parent-to-offspring, but through direct contact or a virus. Once this ancestral cyanobacterium acquired the ability to use PSII and PSI, it forever changed the course of evolution on Earth.

Over hundreds of millions of years, the cyanos slowly proliferated, eventually producing oxygen in the oceans at a rate faster than it could be absorbed, causing mass extinctions of anaerobic lifeforms while paving the way for new metabolic strategies and, eventually, complex multicellular life.

This major episode is known as the Great Oxidation Event, during which oxygen levels began to rise from extremely low levels in the Archean (< 0.001%). Eventually, as cyanobacteria flourished and produced more oxygen, it began to accumulate on land, where the oxidative weathering of iron immediately consumed most of it, turning the land red with banded iron formations. We can see evidence of these banded iron formations in rocks around the world today. Eventually, oxidative weathering slowed and balanced, and free oxygen rose in the atmosphere to 10-40% of what it is today.

Eventually, a major secondary oxidation event, the Neoproterozoic Oxidation Event (NOE), occurred 800–600 million years ago. It’s linked to the rise of marine animals, major glaciation events, and carbon fixation by oxygenic phototrophs exceeding the respiration of organic matter. Together, this raised our oxygen levels to roughly 21% O2, the level in our atmosphere today that supports life on Earth, including our own.

Cyanobacteria Today

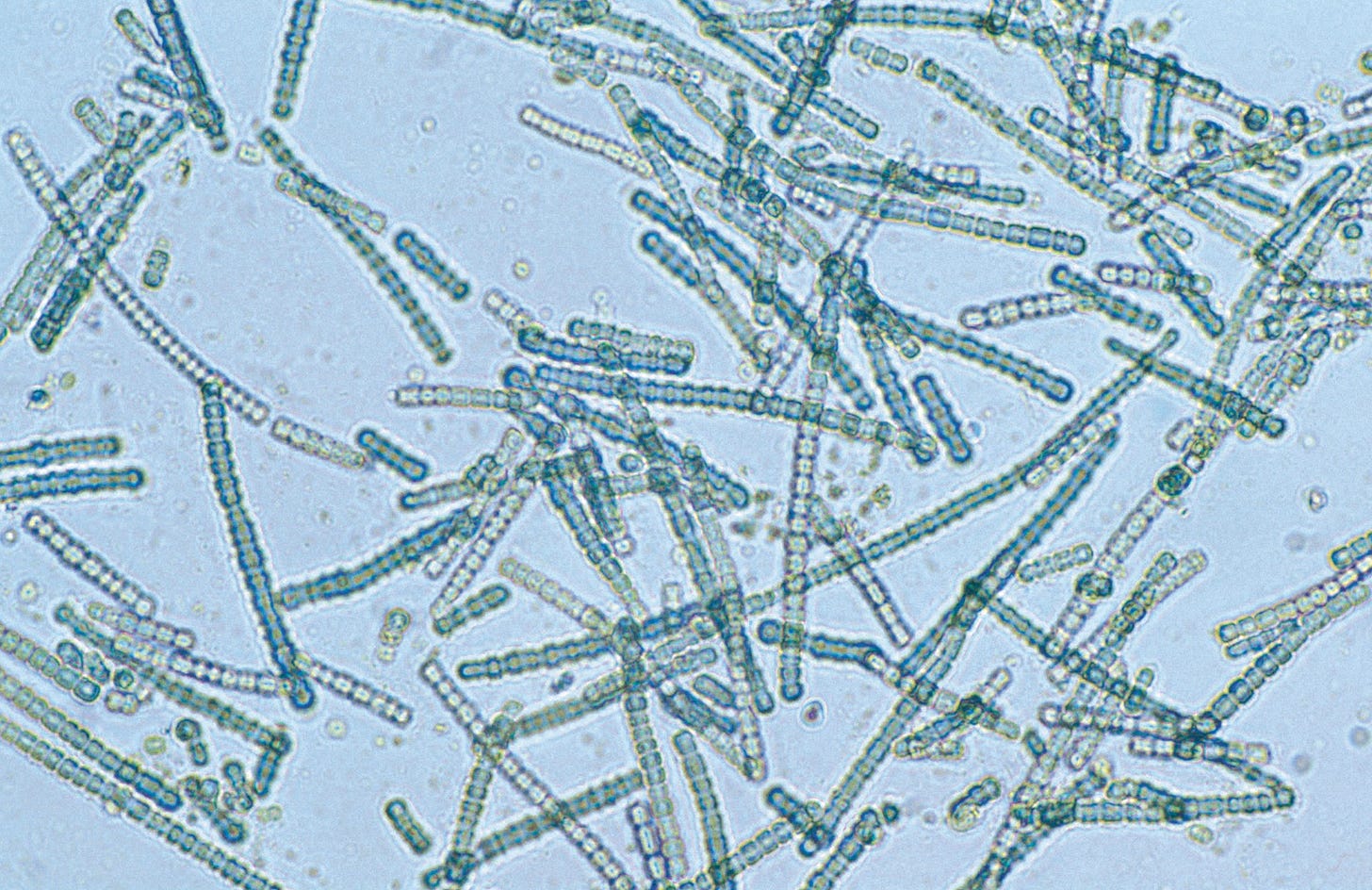

Cyanobacteria are incredibly successful organisms that are still found everywhere today. They live in our freshwater environments, ponds, damp soils, brackish water in estuaries, and many tolerate salinity, thriving in our oceans. They are just as important now as they were during the GOE. For instance, just one species, Prochlorococcus, a cyanobacterium in our oceans, produces about 20% of our planet’s oxygen.

They also often thrive in extreme environments like polar lakes and hot springs, and even inside rocks. Others tolerate desiccation and ultraviolet radiation. They often form biological crusts in arid and semi-arid deserts, where few organisms can survive. Still others proliferate in man-made environments like fish ponds and bird baths. In short, name an environment on Earth and there will be cyanobacteria living and thriving, having evolved and adapted to whatever conditions prevail.

In Appreciation of The Little Things

I don’t usually think about how biology helps humans. They should not be appreciated as our servants, but rather, on their own merit. But they do regulate carbon by sucking carbon dioxide from the air, fixing biomass, and exhaling oxygen. We often think about the trees as beneficial to stopping the onslaught of disastrous climate change, since they are more relatable, but the tiny cyanos are the thankless ones that we might want to appreciate a bit more. After all, you could say that without cyanobacteria, we would not be here today.